Web/Omni Search In Emacs with consult-web or Ditching the Browser's Default Search Engine

how you can improve your search workflow using Emacs in 2024

In this post, I am going to show you how I am changing my web search habits by ditching the web browser for Emacs tools and particularly my new package consult-web. I have already made a YouTube video (see below), showing some of the important capabilities, so I won’t go through all that details. Instead in this post, I first explain why I am trying to ditch the web browser specifically for web search and then will walk you through real everyday examples with step-by-step screenshots as I am typing it all right here in emacs.

Here is the YouTube video if you want to learn more about the consult-web itself:

Part 1: Why do I do this or “for the love of the books not the librarian!”

Before I show you some examples of consult-web and its potential use-cases, let’s take a few minutes to ask why one should ditch the amazing professionally developed polished web browsers for some random hacky Emacs package in 2024 like a bunch of cave men from 40 years ago? To answer that, I would like you to step back and review how web search has evolved in the past 30 years and its current status in 2024.

From the early days of modern web search with Yahoo, Lycos and AltaVista among others to the rise of Google in the 2000s, to today’s ubiquitous web search everywhere, things have evolved quite a bit and we have already seen a couple of wildly different eras. As we look at web search in 2024, it is nothing like what it used to be back in mid 90s or early 2000s. Today, web search is a key part of our daily life. Whether we realize it or not, we are using web search in one form or another for almost everything we do. You probably get answers on various questions regarding your work, your health, or your hobbies from a search engine or a virtual assistant; you likely find coffee shops, restaurants, popular food or attractions near you as well as directions to those destinations by using a search engine or a digital map service; you likely look for recommendations for movies or recipes or books to read or things to buy on a search engine several times a week if not more. You search for latest news, industry trends, latest sports result, and other topics of the day every day.

Statistically speaking, it is very much likely that you do all that by using Google search, because according to market reports, Google alone owns about 90% of the market, with the next player (Microsoft Bing) only owning ~3% of the market and DuckDuckGo at ~0.4%1! This is a clear case of monopoly with no competing threat, and while I normally would not care too much about the status of markets and companies that own them, in this case the situation is much worse than just having a dominating monopoly, because web search is essentially the gateway to accessing critical information in this day and age. It is essentially the equivalent of putting all the books and magazines and sources of important information in the world in one room and then surrendering the key to the room to one librarian, Google search.

To make things worse, with the rise of AI, we are also increasingly likely to be perfectly satisfied with the situation where we only hear the answer directly from the librarian instead of referring to the original source content ourselves! Add to this picture the fact that at the same time that this librarian has been growing in wealth and power (both from money and information/knowledge it holds), the original content creators, whether journalists, scientists, authors or artists have been financially struggling to make ends meet.

Just take a look at news organizations. Most independent news organizations have been struggling financially and lots of smaller local ones have already gone bankrupt. The bigger national or regional organizations are constantly running fund-raising events and begging viewers, listeners or audience to start supporting them with donation or subscriptions. This has already led to the rise of for-profit news organizations that simply publish anything they get paid for (or anything that agrees with their world view) rather than reporting factual information about the world, and yet even them are increasingly using click-baits, baseless articles like “here is 5 things you can do to be successful…”, or purely entertaining content with little useful information, just to stay profitable as they have been losing their audience to social networks!

Take Wikipedia for another example. It’s a non-for-profit organization that gets most of its funding from donations. That means every year Wikipedia has to hound people and coerce them with emails, calls, messages, etc. just to get enough money to pay the checks otherwise Wikipedia would not be able to sustain the cost of running their servers and providing reliable services in the future. This is despite the fact that in lots of cases the top result from Google Search is simply a link to Wikipedia. To put it simply, the middle man that points us to one source or another collects all the money in ad revenues and the original sources get almost nothing!

The situation gets even worse, when you consider the fact that our web browsers are also owned by the same companies (Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge). Conveniently, these web browsers allow us to do a web search right from the address bar that then sends us to the default search engine (preferably the company’s own web search tool unless you are wiling to go through setting pages and change that!). This means that we would almost never directly go to the original creator’s website anymore (unless Google or Bing send us there!) When was the last time that you opened Wikipedia and searched for something on their website rather than Googling it? Again, add the quick rise of generative AI (like chatGPT, and Google Gemini) to this picture and soon the address bar in the browser will give us a direct answer without even having to send us to any other references or original sources anymore! In other words, the search engine and AI companies are going to take (a.k.a. plagiarize) the content form the original authors (journalists, scientists, artists, writers, public databases, …) and claim it simply as their own! This would mean that these companies will grow bigger and more powerful while all the original content makers will continue struggling financially and eventually will either fold or compromise the quality of their content (by allowing some paid-for or empty commercial content) to survive.

Furthermore, without any public alternative (meaning open source software or tools/software owned by a public entity like the governments), there is almost no accountability when something goes wrong and there is no guarantees that the services will continue as we expect. In the past decades we have seen big tech companies simply stopping the support for useful tools and services, or replacing free or reasonably priced tools with expensive subscription models (think of RSS feeds, or Gmail Workspace apps, or desktop apps from adobe that are now subscription only, …). These companies can simply do whatever they decide even though it can have very important consequences on our everyday lives. We need public alternatives that can be held accountable and for that the public services have to retain their users otherwise they won’t be able to justify the cost of maintaining the service.

For example, consider searching for academic literature and scientific papers. In the past decades, PubMed has perhaps been the most reliable service and the go-to tool for looking at scientific publications (especially in the medical and life sciences). It’s a publicly owned database provided and supported by NIH for free without ads and without the influence of powers and politics. However, in the last decade, Google Scholar, has gradually become more and more popular and through clever integration with other tools such as the browsers’ address bar and browsers’ extensions, it has gradually been replacing PubMed. I am a full time scientist and read several papers a week and yet I do not even remember the last time that I went directly to PubMed to search for something unless Google sent me there! It’s just so much easier to open the browser and start typing in the address bar. While on the surface this is yet another useful service from the browser and the search engines, in reality this means that PubMed can slowly lose its relevance and eventually it may not be justifiable for NIH to even maintain the service. Just imagine that in a few years, Google scholar will be able to directly fetch figures and show relevant paragraphs and statements from the papers (with or without the need to even mention the reference), and PubMed could simply become a tool of the past! This would of course be a terrible outcome because we would lose a great publicly owned database and service that come for free and without advertisement or commercial influence to a private entity that will only be serving its share holders’ interest. Such entity would simply be “too big to fail” (if not already); would not feel any accountability to be transparent about how it fetches the results or sort them; would share what it does or does not promote; and etc. This entity would also be able to decide how to monetize the content whether by charging the users or promoting sponsored or popular content (as Google is now doing with web search despite their original approach just a decade ago) and in principle can decide to abandon all the important checks and balances in the scientific community for rigor and validation, by popularizing whatever content it deems accurate. In my opinion, whether such entity would ever chose to do the right thing or the wrong thing is irrelevant. We should simply not allow such entities to come to existent and become so powerful without checks and balances to begin with. In other words, if we simply do not surrender the key to all the knowledge and information in the world to a single librarian today, we won’t have to worry or argue about whether the librarian is going to be a saint or a sinner later, and we should all do this for the love of the books and not for our feelings about the librarian!

Now all that said, let me be clear that I do not subscribe to the mentality that “big companies are just evil” and do not have anything against Google or any other big tech companies in particular. What I do not like here is the accumulation of power through not only revenues but also knowledge of our information (our interests, our location, our habits, our shopping list,…) in single entity (or a few). Even if these entities end up being just a bunch of benevolent royals, accumulation of power and knowledge in them would mean that they would stop innovating since nobody can really threaten their monopolies and the tech will simply get stagnant. We need the tech to solve far more important problems than matching you with the right advertisement, and if the tech companies stop investing in important innovation and basic science (as many of them already have), we would not be able to solve important challenges like global warming or healthcare issues of our aging population.

For this reason, I am trying to change my own personal habits by ditching the source of the problem, the browser and its address bar, as much as possible. I made consult-web, so I can directly and easily fetch results from many sources (whichever I like to, but hopefully original sources) by calling their APIs (even if they charge me a little bit of money for using their APIs). Whenever possible, I would rather directly get the information from the content creator if they provide it to me in a way that is convenient and does not need to compromise too much in efficiency or time. Of course for practical reasons, I would still need to rely on a search engine for lots of other things and for that I am trying to support smaller search engines that are seemingly independent from Google like Brave Search so that I don’t solely rely on Google for every piece of information I need.

If you have followed my previous posts, I have already written about some other Emacs packages I made (like consult-gh and consult-mu) as well as other work flows in emacs, which all have been toward building an integrated system of packages and tools that decrease my dependence on the web browser. consult-web is yet another piece of this puzzle. It allows me to quickly get information from different web sources (search engines, encyclopedias, public databases, …) as well as local sources such as my org and org-roam notes and run actions on the candidates through embark actions. As a result, I can quickly find ad-free information on any topic and use a combination of emacs packages and my own elisp hacks to get work done efficiently and with the least amount of distraction. In fact after using consult-web for a few weeks, I can tell you that, at least for my use-case, consult-web has been much more efficient than using the browser. This is mainly due to the coherent flow inside emacs and the consistency of key bindings and environment as well as the lack of distraction (ads or contents being constantly shoved in my face). While the seemingly polished, professionally developed, software tools like the web browser might look better and feel more natural, after getting used to it, consult-web has been proven much more better than I originally anticipated. It allows me to customize things to match my specific needs and integrate different pieces of my tasks into one coherent flow by combining multiple Emacs packages and embark actions. In the next section, I will share two examples of this to show you how I use consult-web in real everyday scenarios.

Part 2: Examples or “enough with your nonsense philosophical arguments, show me the real world examples!”

In this part, I am going to show you some examples of workflows that I can achieve using consult-web along other Emacs packages.

Finding and Using Emacs Packages

Recently, I was looking for a way to add YouTube videos and subscriptions to my Elfeed feeds. This is something that I find myself doing all the time. I realize there is something missing in my workflow and I want to integrate it into my Emacs flow, and therefore I have to go down the rabbit hole to find the right package and figure out how to configure it and so on. In this case I wanted to reduce the amount of time I would be spending on YouTube with its notorious never-ending content suggestion and just focus on the content I like/need to watch, and I also wanted to be able to get some transcripts to preview what the video is all about in text rather than watching the whole video to see if it is indeed worth watching. I knew that there was some packages and also some good blog post on this topic from memory but I could not remember the name of the package or where I saw the blog post, so I had to do some web search but instead of going to the browser and typing in the address bar I used consult-web this time.

- First, I used consult-web to do a broad search for “adding youtube videos to elfeed” by using the command

consult-web-dynamic-omni. This would include not only looking at search engines (like Brave search) but also directly looking at StackOverflow, YouTube, and other online sources as well as in my own org-roam notes to see if I have saved any notes on the topic from before. This can all be done with one command in consult-web:

(consult-web-dynamic-omni)

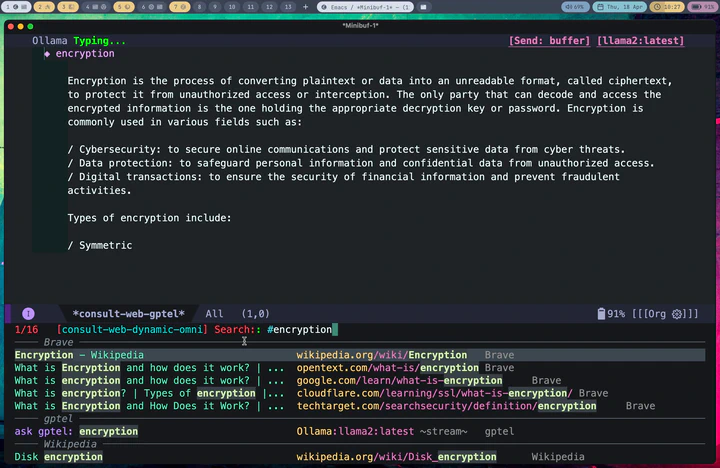

In fact, let me show you a screenshot of that right here as I am writing this post in Emacs:

As you can see, in this case I did not have any previous notes, so I only got responses from Brave and gptel AI assistant.

- Then I look at consult-web results and explore different candidates inside Emacs using consult-preview. In this case, the top two results are the ones I was mostly interested in, but I decided to take a look at what gptel (a.k.a. the AI chatbot) had to say about the topic because that might give me some interesting starting point hopefully with references if I use the right AI backend) already. In the screenshot below, I move the cursor to that option in the minibuffer and use consult-preview to see the response from the AI chatbot:

That answer looked interesting, but I quickly realized that it was mostly AI hallucination (but not entirely!) The function elfeed-summarize and the variable elfeed-show-summary do not exist (at least in my version of Elfeed). However, the part about adding a YouTube feed to Elfeed does work. So the simplest solution could just be to add the YouTube channel as a feed as suggested by the AI hallucination. But that would not add the transcripts and other things I wanted.

For a better solution, I had to go back to the old-school way and use reliable human sources like irreal’s blog post and read through actual GitHub documentation for elfeed-tube. In the screenshot below, I move the cursor back to the candidate for the blog post and use consult-preview again to see the page in xwidget-webkit.

As you see, Irreal’s post had links to two other sources, but since I am not sure if I can trust some random websites I do not know, instead of opening them inside Emacs, in this case I decided to jump to the browser using embark actions to look at those sources. The first one did not exist anymore, but the second one had some useful tips and tricks and showed adding YouTube feeds to Elfeed. However it did not really cover getting transcripts form YouTube either. Using the browser for this viewing of web pages is fine because in this case I immediately jump back to Emacs, and I do that because now that I have consult-web, it’s actually easier to continue from Emacs rather than staying in the browser and redoing the search in the browser.

Next I look at the elfeed-tube package by karthink. In the screenshot below, I again use consult-preview to see the GitHub page in xwidget-webkit and once I confirm that this is indeed the right package to look at, then I pass the GitHub repo’s name to my consult-gh package.

- Next, I use my package consult-gh for looking at the GitHub repo. Here, the embark action code that passes the repo to consult-gh looks like this:

(defun consult-web-embark-open-consult-gh (cand)

"Search github for repo in candidate by using `consult-gh-search-repos'."

(when-let ((url (and (stringp cand) (get-text-property 0 :url cand))))

(if (string-match ".*github.*" url nil nil)

(let* ((urlobj (url-generic-parse-url url))

(path (url-filename urlobj))

(repo (string-join (take 2 (cdr (string-split path "/"))) "/"))

(issue (if (string-match ".*\/issues\/\\([[:digit:]]*\\)" path)

(substring-no-properties (match-string 1 path))))

(pr (if (string-match ".*\/pull\/\\(?1:[[:digit:]]*\\)" path)

(substring-no-properties (match-string 1 path))))

)

(cond

(pr (consult-gh-search-prs pr repo))

(issue (consult-gh-search-issues issue repo))

(repo (consult-gh-search-repos repo))

(t (consult-gh-search-repos)))

(message "not a github link"))

)))

From consult-gh, I can read the README file directly in an org buffer, which means I can fold/unfold headings and focus on the part I am interested in or copy/execute code directly from this org file!

At this point I am done with what I set out to do. Overall, I managed to quickly find the package I was looking for and got the instructions on how to install and set it up all within Emacs with minimum distraction and rabbit holes. From experience, I can tell you that had I done this in the browser I would have ended up opening a million tabs and getting lost in all sorts of distracting web pages because that’s what one does in the browser. Without the ability to save the results neatly in an embark collect or embark live buffer, you end up opening lots of tabs, then spending/wasting lots of time going through them, and at some point you get lost in them. The problem is that a lot of that is simply by design. The browser shows you websites that are designed to just keep you online so they can feed you more advertisements or content and not to give you the information you need in the quickest and most efficient way, and I personally feel that our browsers themselves are also deigned to enable and amplify this effect rather than to prevent it.

Academic Literature Research

Another good everyday example is researching academic literature. Before consult-web, I would be doing a search in the browser, and naturally just use the address bar and type in search queries, then from the Google search results, I would likely click on the suggestion for Google Scholar and would continue the research in Google Scholar. Because of the convenience of it all, I pretty much stopped using PubMed or any other databases for my research, limiting all my information flow through the filter of Google without even realizing it since it was all built in the browser’s address bar. In addition, when doing the search in the browser, I would have ended up opening many of the results in new tabs and before I knew it I would be drowning in tabs. Eventually I would only read a few of them and would go down some rabbit holes and then give up on the rest because I did not have it all in an organized format. I tried to incorporate Zotero as well as some Emacs tools to improve this but at the end the source of the problem was the browser itsself and how the search engines show a list of results that you cannot easily export, save or organize.

With consult-web, I could resolve both issues. I decided to go back to using PubMed as well as Scopus through their API services, which not only allows me to customize the work flow but also help support public services (like PubMed) or publishers (since Scopus is associated with Elsevier). These are not paid services right now but even just giving them access to my information (about what topics I am interested in) is perhaps better than giving that information to Google and Google only! I can also quickly get the results in an organized format and save them for later so over the next few weeks and can systematically read and review and check them off the list. Here is a quick example of the flow:

- I use

consult-web-scholarto do a wide search in PubMed, Scopus as well as my Org Roam notes since I keep some notes on papers I read there as well. I have also added gptel to my scholar sources since sometimes it helps to get a general description on certain topics from AI chatbots. Here is a screenshot of searching for nanopores (my main topic back in my PhD days):

As you can see I can move around and quickly look at some of the results using consult-preview, and I can also increase the number of results I fetch form PubMed and Scopus. I yet have to implement some more complex filtering features in consult-web (e.g. filter by date, journal, etc.), but it’ll do for now.

- In case of academic publications, I then usually use

embark-exportto save everything in one buffer, so I can then slowly go over each paper and read and decide whether I want to take a deeper look at it or not. If at some point I am tired or have to leave this, I can all the links using embark actions withembark-act-allinto an org file and come back to it later (I demonstrated this in the YouTube video here) so I won’t lose the results and everything remians organized.

In the embark export buffer, I can hit enter to open the link in an external browser. Usually I would be doing this on a wide screen with browser and Emacs window next to each other, or even more conveniently in two emacs buffers (one for the browser and one for the embark-export) in windows next to each other, but here I just jump back and forth:

I can then run embark actions on a candidate for example to add an entry to my Read List so I can go over the paper in more depth later. The Read List in this case is an org agenda file with ToDo headings, and the capture function looks like this:

(defun consult-web-scholar--org-entry (cand)

(if (stringp cand)

(let* ((url (get-text-property 0 :url cand))

(doi (get-text-property 0 :doi cand))

(doi (if (and doi (stringp doi)) (concat "https://doi.org/" doi)))

(title (get-text-property 0 :title cand))

(authors (get-text-property 0 :authors cand))

(authors (cond

((and (listp authors) (= (length authors) 1))

(car authors))

((listp authors)

(mapconcat #'identity authors ", "))

(t authors)))

(journal (get-text-property 0 :journal cand))

(date (get-text-property 0 :date cand)))

(concat

(if title title "\n")

(if authors "%s\n" authors nil)

(if journal (format "in =%s=\s" journal) nil)

(if date (format "published on [%s]\n" date) "\n")

"\n=========================================\n"

(if url (concat (format "[[[%s][URL]]]" url) "\t") nil)

(if doi (concat (format "[[[%s][DOI]]]" doi) "\t") nil)

"\n"

"\n** My Notes:\n"

))))

(defun consult-web-embark-scholar-add-to-readlist (cand)

(with-temp-buffer

(let ((org-capture-templates `(

("d" "Defualt" entry

(file+olp "~/Org/Read.org" "Inbox")

"* READ %(funcall #'consult-web-scholar--org-entry cand) %?"

:empty-lines 1

:immediate-finish t

:prepend t

)

)))

(org-capture nil "d")

)

))

This is mostly a reminder for me to read this paper at some point in the near future. The notes here are for some quick reminders I will add when I capture this task. For actual note taking when I read the paper in depth, I will use org-roam. To do that I use zotra to add a bibliography entry to my main bibliography collection (this can be done either from the candidate in the minibuffer or from the links in the org link). Here is a function for adding a URL using zotra. I add this to embark actions for both URLs and for org-links:

(defun embark-url-add-zotra-entry (url-or-doi)

(zotra-add-entry url-or-doi))

(keymap-set embark-url-map "c z" #'embark-url-add-zotra-entry)

(keymap-set embark-org-link-map "c z" #'embark-url-add-zotra-entry)

Then I can use citar, which uses the same bibliography file as the one I use with zotra, along with citar-org-roam to add notes on the paper in my org-roam collection. This way I have a nice collection of all the papers I have read and if a paper is not in this collection, I know I have not read it in depth yet. I also have detailed notes on each paper I spend time on so I can later come back to it when needed. Furthermore, I can use org-roam-ui, and organize my notes to find connections between papers and topics that help me with finding new areas of interests and coming up with novel innovative ideas for further research. Here is a screen shot:

Closing Thoughts

As I am using consult-web on a daily basis, there are more and more use cases I am finding for it especially with the omni-search, where I can look at results from the search engines next to my own notes and feeds. I only wished I was allowed to use this in my day job but that’s a story for another day. I think for now the two examples I highlighted above are enough to show you some real everyday examples and perhaps encourage you to give consult-web and Emacs-driven workflows a try and see if you can also reduce your dependence on the web browser and your default search engine.

If you read this article and have some opinions you would like to share, you can add comments below or directly message me at contact@armindarvish.com. If you start using consult-web and like it, you can support my work and help me by directly sponsoring me on GitHub or by supporting other open source software especially the ones that enable what I am doing (e.g. Emacs, packages like consult, embark, org-web-tools, gptel, elfeed, magit, and …); and if you agree with what I had to say in Part 1 and would like to support independent sources, then you should consider supporting your local independent news organization, or radio station; or start donating to Wikipedia; or simply go back to using PubMed instead of Google Scholar! Either way, best of luck in your web search journey and hope you enjoy the ride with AI in the years to come!